Loading profile. Please wait . . .

Photuris forresti Lloyd, 2018

Loopy Five Firefly

Federal Protection: No US federal protection

State Protection: No Georgia state protection

Global Rank: G1

State Rank: S1S2

Element Locations Tracked in Biotics: Yes

SWAP 2015 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN): Yes

SWAP 2025 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN): Yes

2025 SGCN Priority Tier: High Conservation Concern

Element Occurrences (EOs) in Georgia: 7

Habitat Summary for element in Georgia: Edges and inlets of ponds or open riparian wetlands with emergent and floating plants

The Loopy Five Firefly (Photuris forresti) is a rare firefly in the genus Photuris that is identified by a unique, five-spot looping flash pattern (Lloyd, 2018). This firefly has only been found a handful of times across three states, with the majority of sightings being in northern Georgia (Joyce, 2023). This species is listed as endangered under the IUCN Red List (Walker & Faust, 2022).

Dr. James E. Lloyd discovered and collected the holotype (the specimen used to describe the species) of this species in 1986 (Lloyd, 2018). In 2018, he formally described the species, remarking that it very closely resembles Photuris tremulans. Both species have an arrow-shaped pronotal (head shield) marking, dark hind coxae (first joint of the leg), and dark elytra (outer wing) usually without wing markings (Joyce, 2023). Loopy Five firefly males measure between 11-12 mm long (Fallon et al., 2022).

In comparison to fireflies in the genus Photinus, Photuris fireflies are generally larger, have long and slender legs, and a head that is visible from above since it isn’t hidden by the pronotum (head shield) (DiTerrlizi, 2004).

Photuris forresti appears physically identical to Photuris tremulans and can only be identified by its unique flash pattern (Lloyd, 2018).

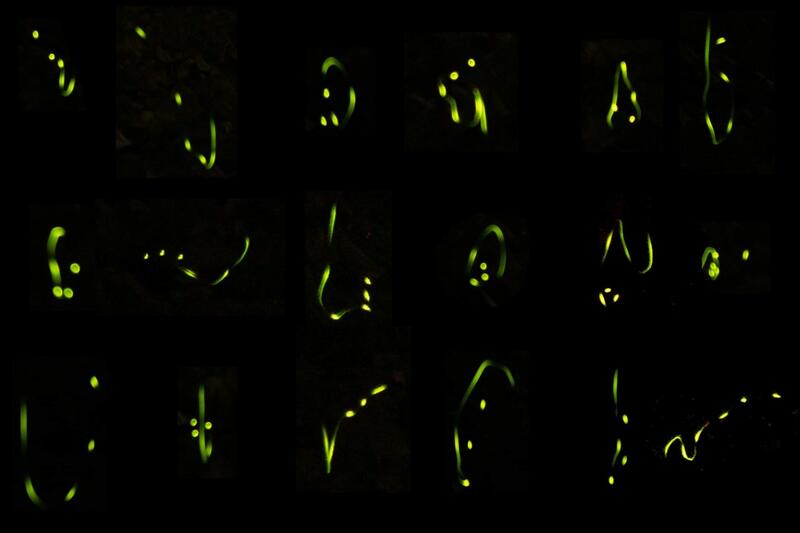

Its flash pattern (FP) closely resembles the FPs of fireflies in the Photinus ardens group, but the Loopy Five Firefly emits a green flash in contrast to the yellow or yellow-orange flashes of its FP lookalikes (Lloyd, 2018). This flash pattern (see life history) is the primary characteristic used to identify this firefly in the field.

This firefly is found in marsh and low grassland habitats (Lloyd, 2018).

Like other members in the genus Photuris, Loopy Five Firefly females mimic the signal flashes of Photinus female fireflies to lure in Photinus males for consumption. This granted them the nickname “femmes fatales”(Eisner et al., 1997).

The larvae of this genus are said to be scavengers and eat a variety of food items including slugs, earthworms, other soft-bodied invertebrates, and plant matter (Bushman, 1984).

The egg-laying and larval stage of the Loopy Five Firefly has not been well documented. Therefore, the genus-level information was used in the following description. Photuris females may deposit a small number of eggs into the soil at multiple sites over time (Lloyd, 2018). After a few weeks, the eggs hatch into larvae (Faust, 2017). The larvae have several body segments each shielded by a small plate of armor. They are luminescent and spend their time scavenging around the damp soil surface for a meal (Lloyd, 2018). They remain as larvae for around 1-2 years (Faust, 2017). When ready to pupate, the larvae burrow underground in chambers where they can remain for one to three weeks depending on the temperature until emerging as adults. (Lloyd, 2018).

Loopy Five males begin flashing from around 25 minutes after sunset and continue for about 2.5 hours (Lloyd, 2018). Their flash pattern is about 2.5 seconds long and consists of 4-7 rapid flashes (Faust, 2017; Lloyd, 2018). These flashes make a vertical loop pattern, hence the common name “Loopy Five Firefly”. Males fly just above the marsh awaiting female response flashes (Lloyd, 2018). The interval between FPs usually lasts 12-26 seconds, and during this interval, males move laterally about 6-8 feet. The adult display period is between mid-May to early July (Joyce, 2023).

Survey after sunset and watch for the flash pattern described in life history. Record flash pattern duration and intervals.

The Loopy Five Firefly has only been observed in eastern Tennessee, northwestern South Carolina, and northern Georgia (Joyce, 2023; L. Faust pers. obs.; Faust and Davis, 2019).

The species was discovered in marshland in Pickens County, South Carolina in 1986 (Lloyd, 2018). It has also been found at another site in Pickens County, SC, and at a site in Jefferson County, Tennessee. Multiple biologists surveyed for this species in 2018, 2019, and 2020 across many states in appropriate habitats, and no additional occurrences were observed (L. Faust pers. obs.). However since 2022, more occurrences have been recorded throughout northern Georgia (Joyce, 2023). This new wave of sightings is encouraging and prompts the need for more comprehensive surveying.

Habitat loss is the largest threat to the Loopy Five Firefly. For instance, the marsh in Pickens County, South Carolina was previously occupied by this species until being destroyed to create a golf course (Lloyd, 2018). Many Pointy Lobed Fireflies (profile linked here: https://georgiabiodiversity.org/natels/profile?group=arthropods&es_id=432423) were also found at this location. A follow-up survey was conducted in 2018 and no Loopy Five Fireflies (or Pointy Lobed Fireflies) were found (Lloyd, 2018; L. Faust pers. Obs.). Therefore, the protection of marshland habitats and the Loopy Five Firefly go hand and hand. Unfortunately, marshlands are threatened by several factors including draining, dredging, damming, and redirecting waterways for development and flood control, runoff from agricultural or urban areas, invasive species, and vegetation damage (EPA, 2001).

Light pollution is another notable threat to this firefly and is caused by unnatural light sources at night such as street lights, car headlights, lights from buildings and houses, advertising, etc. (International Dark-Sky Association, 2017). Many firefly species are nocturnal and use light flashes to communicate and be seen by mates (Lloyd, 1971). Thus, these fireflies are particularly vulnerable to artificial light interrupting their signal flashes. Several studies have supported that light pollution interferes with firefly reproductive behavior and abundance (Owens & Lewis, 2018; Lewis et al., 2020). For instance, light pollution has been shown to reduce courtship flashing in multiple firefly taxa (Yiu, 2012; Firebaugh & Haynes, 2016; Hagen et al., 2015; Costin & Boulton, 2016). Therefore, artificial light sources disturb natural firefly behavior and contribute to their decline.

Pesticides are ranked as the third major threat to fireflies worldwide (Lewis et al., 2020). Fireflies can be exposed to pesticides through aerial spraying, contact with affected soil or water, or consuming contaminated prey. The egg, larval, and pupal stages are particularly at risk given the potential for long-term exposure to contaminated soil. Pesticides can indirectly affect fireflies by killing and poisoning larval prey species. Adults may also be directly affected by mosquito spraying which occurs at dusk when fireflies are most active (Lewis et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2007). Pesticides can not only cause mortality but also harmful sublethal effects (Joyce, 2023). For instance, one study found reduced feeding and soil chamber construction in fireflies, P. pyralis and P. versicolor, following pesticide exposure (Pearsons et al. 2021). In general, pesticides endanger fireflies and can have multiple negative effects depending on factors like exposure level or pesticide type.

SNR- Unranked — National or subnational conservation status not yet assessed.

More surveying is needed to determine a proper status.

Conservation of wetland habitat is vital to the well-being of this species. Wetland habitats should be protected from human activities such as dredging, damming, drainage, and redirecting waterways. Pollution sources should be contained and limited as much as possible.

Reduce light pollution by turning off unnecessary outdoor lights and keeping blinds and curtains closed at night. Spread the word to inform the public about light pollution and its effect on fireflies and other animals.

Reduce pesticide use, especially in or around wetland habitats.

Because larvae live in the soil, leaf litter, and other ground debris until adulthood, reduce any unnecessary lawn maintenance.

Buschman, L.L. (1984). Larval biology and ecology of Photuris fireflies (Lampyridae: Coleoptera) in Northcentral Florida. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 57(1): 7-16.

Costin, K. J., & Boulton, A. M. (2016). A field experiment on the effect of introduced light pollution on Fireflies (coleoptera: Lampyridae) in the Piedmont region of Maryland. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 70(1), 84–86. https://doi.org/10.1649/072.070.0110

Davis, R., Peterson, R., Macedo, P. (2007). An ecological risk assessment for insecticides used in adult mosquito management. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 3, 373–382

DiTerrlizi, T. (2004). Genus photuris. BugGuide.Net. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://bugguide.net/node/view/8210

Eisner, T., Goetz, M. A., Hill, D. E., Smedley, S. R., & Meinwald, J. (1997). Firefly “Femmes Fatales” acquire defensive steroids (lucibufagins) from their Firefly Prey. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(18), 9723–9728. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.18.9723

Environmental Protection Agency. (2001). Threats of Wetlands. EPA. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-02/documents/threatstowetlands.pdf

Lewis, S. M., Wong, C. H., Owens, A. C., Fallon, C., Jepsen, S., Thancharoen, A., Wu, C., De Cock, R., Novák, M., López-Palafox, T., Khoo, V., & Reed, J. M. (2020). A global perspective on Firefly extinction threats. BioScience, 70(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz157

International Dark-Sky Association. (2017). Light Pollution. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.darksky.org/light-pollution/

Lloyd, J. E. (2018). A naturalist's Long Walk among shadows: Of North American photuris: Patterns, outlines, silhouettes ... echoes. at the Bridgen Press.

Lloyd, J. E. (1971). Bioluminescent communication in insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 16(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.16.010171.000525

Lloyd, J. E. (2005). Pointy-lobed Firefly done - South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved October 17, 2022, from https://www.dnr.sc.gov/cwcs/pdf/PointylobedFirefly.pdf

Firebaugh, A., & Haynes, K. J. (2016). Experimental tests of light-pollution impacts on nocturnal insect courtship and dispersal. Oecologia, 182(4), 1203–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-016-3723-1

Fallon, C., Walker, A., Lewis, S., & Jepsen, S. (2022.). State of the fireflies of the United States and Canada:: Xerces Society. State of the Fireflies of the United States and Canada: | Xerces Society. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from http://www.xerces.org/publications/scientific-reports/state-of-fireflies-of-united-states-and-canada

Faust, L. F. (2017). Fireflies, glow-worms, and lightning bugs: Identification and natural history of the fireflies of the eastern and Central United States and Canada. The University of Georgia Press.

Faust, L. F., & Davis, J. (2019). A new species of Photuris Dejean (coleoptera: Lampyridae) from a Mississippi Cypress Swamp, with notes on its behavior. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 73(2), 472. https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065x-73.2.472

Hagen, O., Santos, R. M., Schlindwein, M. N., & Viviani, V. R. (2015). Artificial night lighting reduces firefly (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) occurrence in Sorocaba, Brazil. Advances in Entomology, 03(01), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.4236/ae.2015.31004

Joyce, R., Selvaggio, S., & Fallon, C. (2023). (rep.). PETITION TO LIST The loopy five firefly Photuris forresti (Lloyd), 2018 AS AN ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT. Xerces Society. Retrieved from https://xerces.org/sites/default/files/publications/Photuris%20forresti%20ESA%20petition_2023-03-21.pdf.

Owens A., Lewis S. (2018.) The impact of artificial light at night on nocturnal insects: A review and synthesis. Ecology and Evolution, 8, 11337–11358.

Pearsons, K. A., Lower, S. E., & Tooker, J. F. (2021). Toxicity of clothianidin to common. Eastern North American fireflies. PeerJ, 9. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12495.

Walker, A. & Faust, L. (2022.) Photuris forresti. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T199788991A199817215. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T199788991A199817215.en. Accessed on 28 February 2023.

Yiu, V. (2012). Effects of artificial light on firefly flashing activity. Insect News , 4, 5–9.

Reagan Montalvo

4/13/2023